What is ART for?

Breathing, embodying

Honouring nature

What is art for? is a social engagement project that features the work of 81 artist/participants from around the world, who in the summer of 2020 created and contributed works that consider the role of art in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic. Launched via my personal Facebook page in response to the anxieties of disease and the isolation of the spring’s lockdowns, What is art for? invited anyone interested to request a free kit of optional art materials, and to send in a creation to be part of a collaborative exploration of the question: what is art for in this time of pandemic?

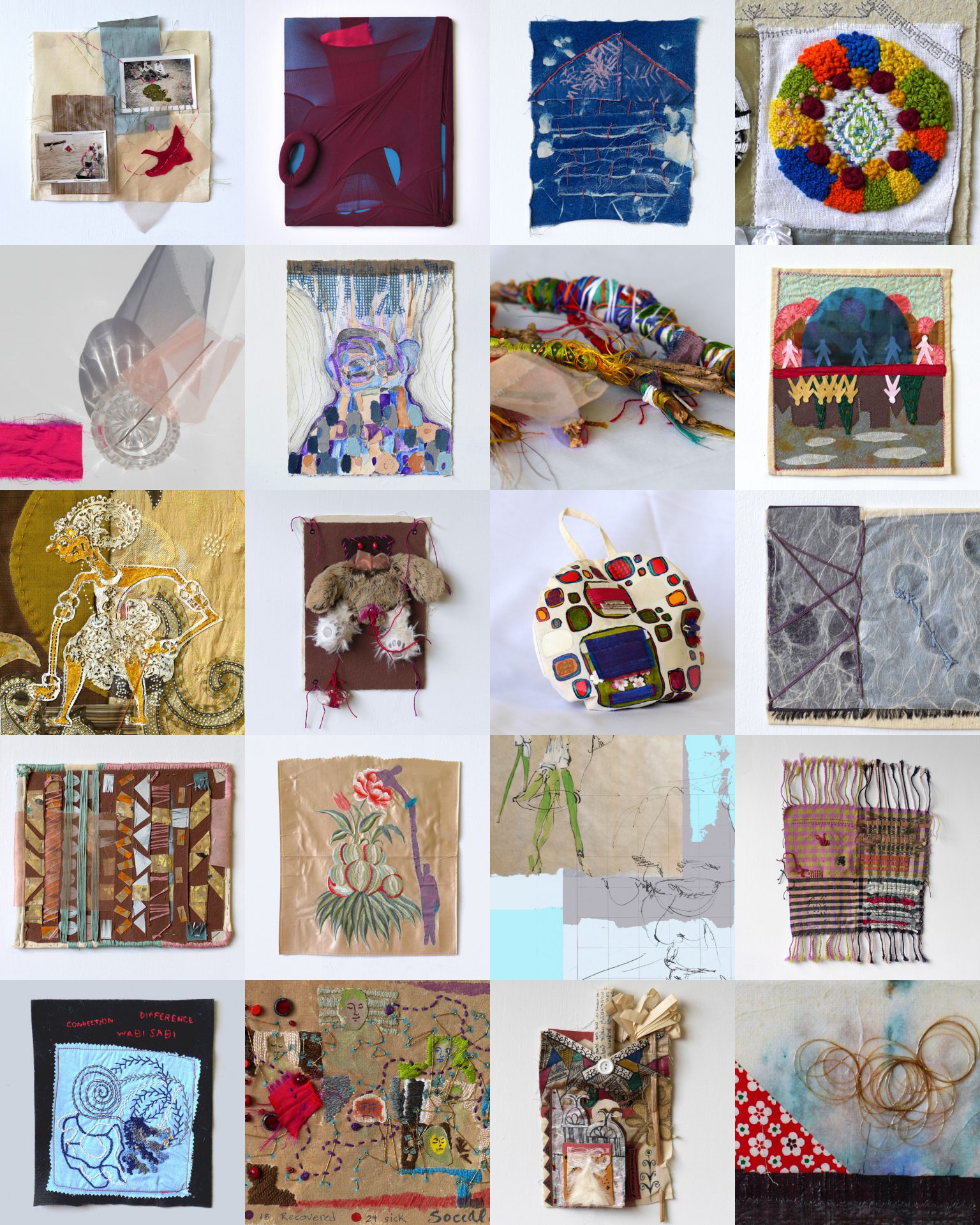

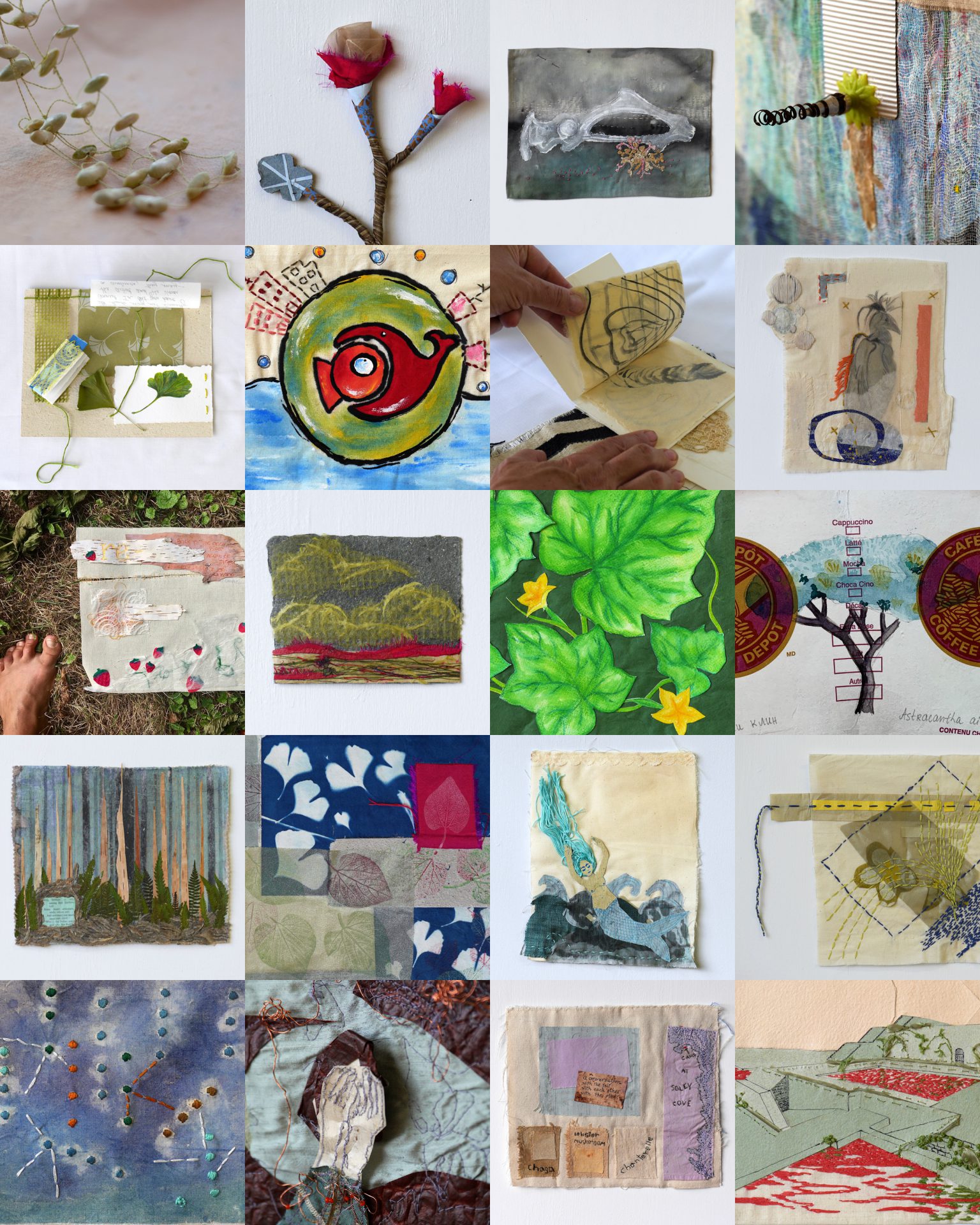

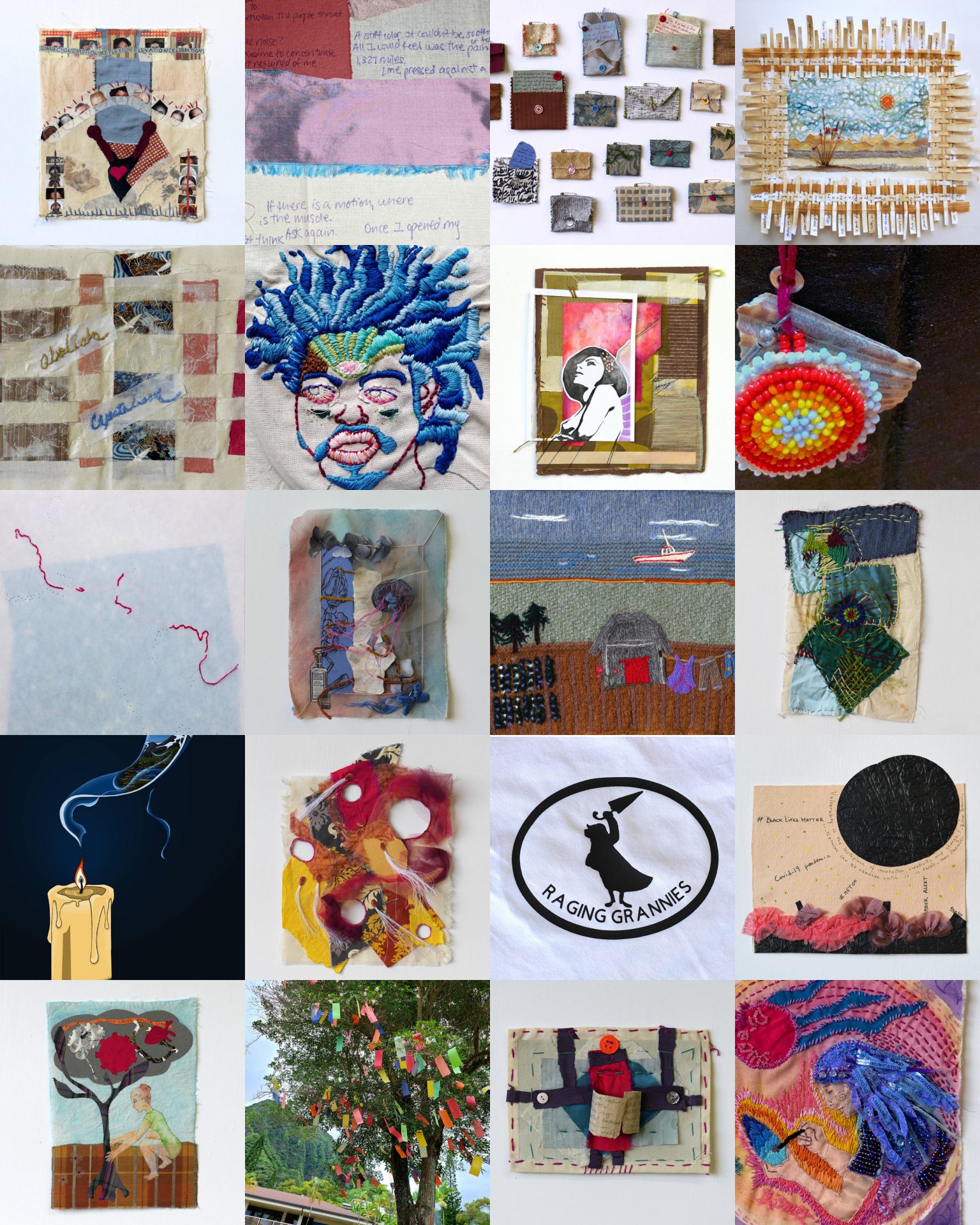

The answers are reflected in the four grids: breathing/embodying, comforting/connecting, honouring nature, and raging/dreaming/making change.

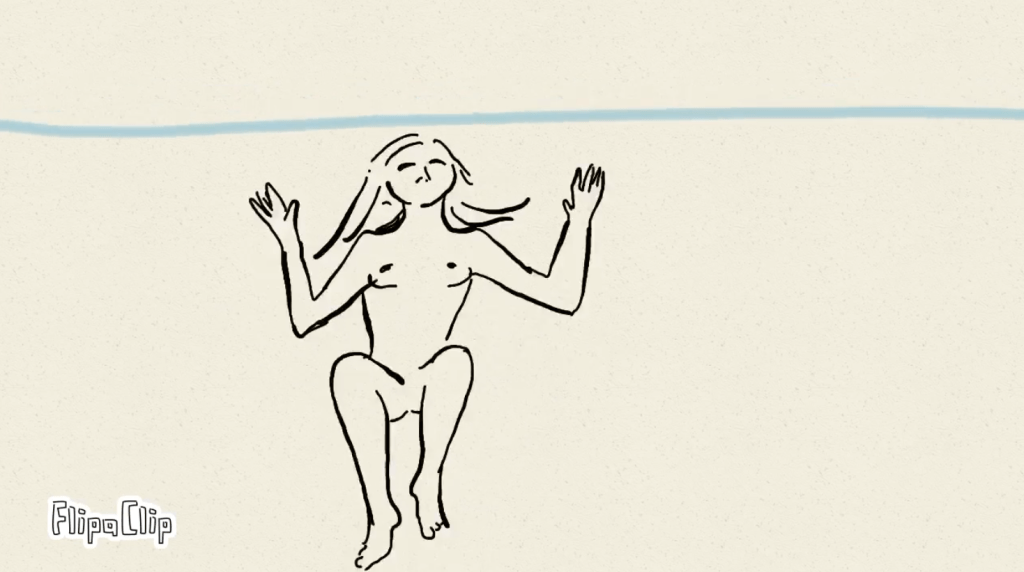

Two video contributions supplemented the still (digital and material) works, one (by Marie-Pier Viens) is part of the breathing/embodying theme, while the other (by Marc Nerenberg) is part of the raging/dreaming/ making change grouping: I saw these as book-ending the collaboration.

On view

What is art for? is in exhibition at the Warren G. Flowers Art Gallery at Dawson College, from February 5 through March 14, 2026, with an accompanying maker space. Gallery visitors are invited to offer their own response to the question “what is art for?” using provided materials with their imaginations provoked not only by the continuing resonance of the artwork on show but by new challenging realities. This exhibition is accompanied by catalogues in English and French, featuring texts by Kathleen Vaughan, Natalie Olanick (curator for the Flowers Gallery), and Pohanna Pyne Feinberg, and text contributions by Jacob Le Gallais. The catalogue was created with special funding by the Gail and Stephen A. Jarislowsky Institute for Studies in Canadian Art.

The Project’s Origin Story

On March 11, 2020, the World Health Organization declared the coronavirus COVID-19 a pandemic, reflecting the global reach of this contagious and lethal disease. By March 12, schools, businesses and institutions worldwide started to shut down and governments required that people to stay home. It was a strange and isolating time. I missed the public encounters of teaching and community-based art-making, as well as the dynamic exchanges of the art world – a local exhibition of my works was closed a week after it opened, the works still visible through the ground floor window. As the weeks went on, I began to consider what art making might be for in this unprecedented and challenging time. I was sure other artists were wondering, too.

On July 8, I launched the invitation to participate in What is art for? with a public Facebook post wondering whether I’d get 20 inquiries in response. To my thrilled surprise, by July 13 I had reached 100 requests – the limit of my resources – from people I knew personally, Facebook acquaintances, and strangers who’d seen the posts and wanted to be part of the activity. In response, I assembled and mailed individualized envelopes that included handmade paper (from Papeterie St-Armand and the Japanese Paper Place), an assortment of tactile fabrics (silk, organza, muslin and cotton), two skeins of embroidery thread and a large-eyed embroidery needle, stuck into a piece of fuchsia silk. The packages were a joy to assemble. Each represented a unique and (I hoped) beautiful combination of colours and textures, with materials drawn from my own stash supplemented by additional purchases.

Also included was an addressed return envelope, with postage paid for Canadian participants, so that the works could come back to me by the requested date of August 15. Mail moved more slowly in those days – still does – as postal and delivery services struggled to keep up with surging demand and develop protocols to keep their workers safe and physically distanced as they provided what was newly recognized as an essential service.

By September 1, 2020, I had received contributions from 81 collaborators. Some works were material, others digital, including two videos and an animation. Most participants integrated some or all of the materials they’d received in the kit; some sent works made from their own supplies; others e-mailed photos of work in situ and digital art. 51 contributors came from the province of Quebec, with the remaining 30 from seven other Canadian provinces, six American states, and four other countries. These works are showcased here, grouped by me into the four themes – broad categories of response to the question. I determined the themes based on what I discerned in the works, which in some cases fit squarely into one category, and in others touch on more than one.

The still works divided quite equally into four quadrants of response, enabling their curation into four grids. I kept the two video works separate from the grids, in view of their special time-based status.

The grid has been vaunted by art theorist Rosalind Krauss as a modernist icon that aims to subdue the natural world, and more recently explored by Hannah B. Higgins as a changeable thinking tool enacted variously throughout the record of human history, from the ancient Mesopotamia’s bricks to the futurity of the World Wide Web.* I draw happily on those discourses in using the grid here, as a way to bring together a wide variety of works. In their juxtaposition and inclusion sometimes through full frame images, sometimes through detail shots, I aim to invoke a descant of discussion that adds a choral turn to the individual voice of each contributor.

Discussion of each theme can be found on the page that showcases its grid, where the artists whose works reflect that theme are named. The grids on the theme-related pages are dynamic, the thumbnails in the grids ‘clickable’ to access individual artists’ pages, complete with documentation photographs and any (optional) statement.

Documentation photographs courtesy of Veronica Mockler unless otherwise noted; Veronica also collaborated on the layout of the grids.

In addition to being showcased here, What is art for? is part of a book project on socially engaged art in Québec being produced by Centre d’art actuel Skol and Centre Sagamie, with publication anticipated for early 2022. It is hard to reckon that by then we will be almost two years into the pandemic; at this time of writing, we are at the one year anniversary. With more than 2.5 million deaths now recorded worldwide, and people around the world experience a continuing patchwork of lockdowns and curfews, as well as many job losses (the arts sector being particularly hard hit), the collaborating artist’s responses to the project’s initiating questions seem as defiantly meaningful now as when they first created them. Who would have imagined?

* For more on grids see Rosalind E. Krauss, “Grids,” in The Originality of the Avant-Garde and Other Modernist Myths (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 1999) and Hannah B. Higgins, The Grid Book (Cambridge, MA: MIT Press, 2009). Note that Krauss’s essay was originally written in 1979, 30 years before Higgins’s book.