August 2017: The fast moving St. Lawrence River at the eastern edge of Pointe-St-Charles.

Walk in the Water | Marcher sur les eaux (2016-2020) is a research and creation project that uses visual art and oral history to explore the St. Lawrence River’s shoreline at the de-industrialized Montreal neighbourhood of Pointe-St-Charles, from environmental and social perspectives. The project draws on current and previous writings and interviews with local residents as well as with experts from the disciplines of urban planning, history, political ecology, botany, literature, sanitary engineering, environmental studies, water ecologies, and more.

The purpose of Walk in the Water | Marcher sur les eaux is to raise awareness of the specifics and complexities of our River, of some of the many ways that people can and do connect with its waters and creatures, and to encourage affection and advocacy for this remarkable environmental and cultural feature of central/eastern Canada.

Flowing more than 1200 kilometres from freshwater to salt, from its origins at Lake Ontario to the largest estuary in the world at the Gulf, the St. Lawrence River is an essential natural and cultural resource. The shores of the river and its tributaries are home to over 80% of Québec’s population, and 50% of Quebeckers get their drinking water from these watercourses.

Walk in the Water takes multiple forms, including:

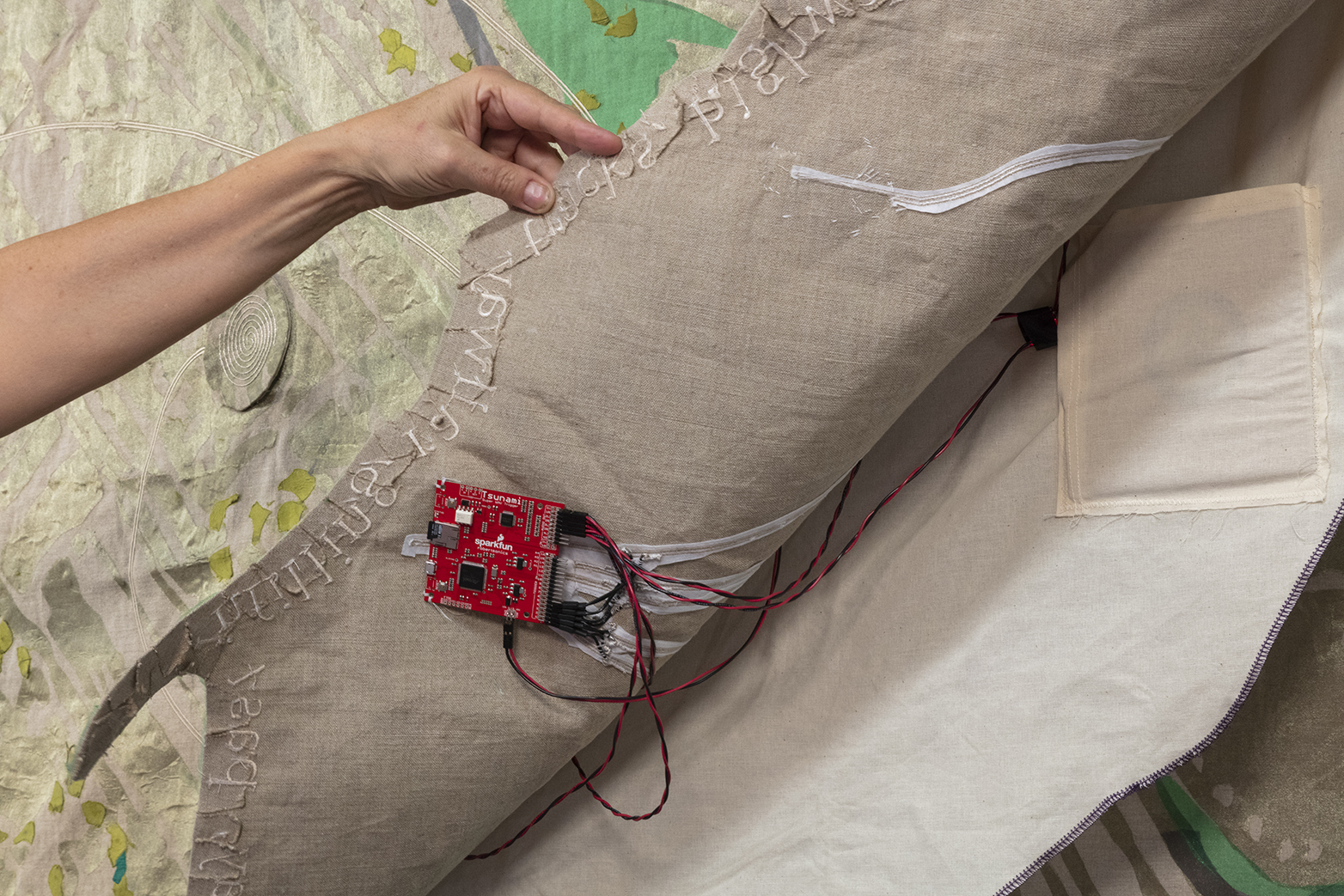

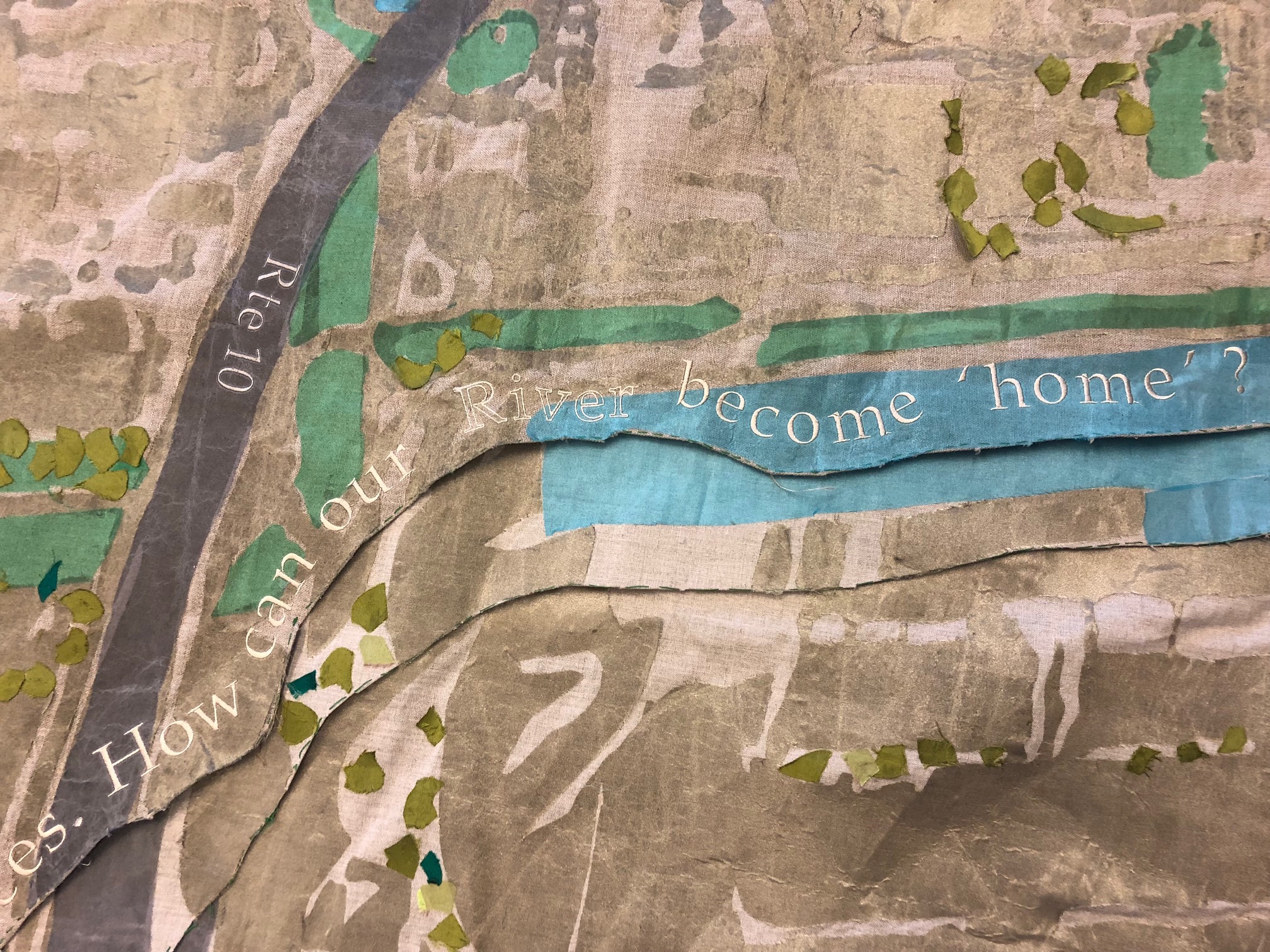

- a wall-sized textile map of the shoreline’s changes, which features multiple layers of pieced and embroidered cloth denoting the flowing river and its changed boundaries, as well as touch-activated audio excerpts of river stories.

- an audio walk that juxtaposes features of the original (as mapped in 1801) and the current shoreline, and includes excerpts from interviews done with River excerpts and citizen activists, as well as the hydrophonically recorded submerged voice of the St. Lawrence River itself.

Walk in the Water is shown via exhibitions and at public events (e.g. organized group walks), discussed in academic and general interest writing (including an exhibition catalogue), and its audio walk is available via digital download from this website.

Walk in the Water builds on Kathleen Vaughan’s ongoing work based in ‘the Point’ and her interest in and collaborations about water and its meaning (for instance, via the Waters Lost, Waters Found Working Group at Concordia University) and encompasses related water-y projects such as Gardens of Water (2017).

Walk in the Water | Marcher sur les eaux was conceived by Kathleen Vaughan and developed with input from and the assistance of Jill Bennett, Joanna Donehower, Lizzie Grater, Emma Hoch, Ryth Kesselring, Jeannie Kim, Jacob Le Gallais, Philip Lichti, Nicole Macoretta, Gen Moisan, Kay Noele, Martin Peach and Eric Powell, as well as special funding from Concordia University.

Background to the project

I am told that the Mohawk name for the St. Lawrence River is Kaniatarowanenneh, meaning “big waterway.” Montreal and the River are located on the traditional and unceded territory of the Kanien’keha:ka or Mohawk peoples, and this island archipelago has long served as a site of meeting and exchange amongst nations and peoples. (See Darren Bonaparte’s writings for a brief history of First Nations habitation of the St. Lawrence.)

Once, the St. Lawrence River flowed directly alongside – and would seasonally flood – the low-lying, boggy land of the part of Montreal now known as Pointe-St-Charles. When European settlers arrived in the 1500s, an actual Point reached into the river, creating a sheltered upriver cove at which was later built the Maison St. Gabriel. This 300-year-old fieldstone house, centrepiece of the farm of the Sisters of the Congregation of Notre Dame, was a stopping point for the young French immigrant women known as the ‘Filles du Roi’ | King’s Wards who crossed the seas in the 1660s to make this land their home. The Nuns and their wards used the nearby island (Nuns’ Island | Île des Soeurs) as a planting site, and would call their requests for harvest across the waters. But the River is no longer in view of the house, which still stands.

Over the last 200 years, the shoreline itself has been dramatically changed as a result of dumping (the area once served as the city garbage dump) and infilling (with ground excavated to create the Lachine Canal in the 1820s and 1840s and the Montreal subway system in the 1960s). Now, much of the Point’s terrain by the river is described as being contaminated soil, not fit for human habitation. Instead, it is home to Industrial building of railway lines, Highway 10 and a Technoparc, which means that the river is hard to access from the residences of the Point. It takes a determined human visitor to get to this part of the island – and yet non-human life continues.

Montrealers have strong feelings about our River, as shown in November 2015, when many responded with anger and dismay at the City’s proposal to dump raw sewage directly into the St. Lawrence (at the eastern edge of – or just downriver from – Pointe-St-Charles) in order to perform essential maintenance of holding tanks. Scrutiny by federal and provincial government environmental watchdogs delayed but did not stop that dump, which some locals recall with shame. Many Pointe-St-Charles residents dream of a day when their shoreline is once more accessible, and given the same loving treatment and public investment as Verdun to the west, with its boardwalks and beaches, and the parks and greenspaces of Cité du Havre and Île-Ste-Hélène to the east.

What is the Pointe-St-Charles riverscape now? What do we think of when we imagine this little-known shoreline? What would it mean to walk in the water? How can our River become ‘home’?

The Point’s shoreline shifts were first brought to my attention via a 2010 article in Spacing Montreal, which mentions prior research by the Société d’histoire de Pointe-St-Charles and local architect, Mark Poddubiuk.